On 7 December 2020, Slovenian Minister of Economic Development and Technology Zdravko Počivalšek made a statement about the second lockdown in Slovenia. In television programme Studio City he said that generally speaking Slovenia has had one of the longest “lockdowns” in Europe. He also stated Slovenia had a thorough system that, in his opinion, did not work. This statement is mostly true.

Zdravko Počivalšek is Slovenian Minister of Economic Development and Technology. He became the minister in 2018. He is also the president of political party Stranka modernega centra – SMC. During the coronavirus pandemic, Počivalšek was criticized for the large government purchase of protective masks, which were not suitable for use by health professionals. Although many called for his resignation, the minister did not do so.

On 7 December 2020, he was a guest on a television programme Studio City broadcasted by RTV Slovenija, where they discussed coronavirus measures, lockdowns and current political situation in the country. During the show, Počivalšek made the statement, that Slovenia had “one of the longest” lockdowns in Europe. He continued that the system of a lockdown is a “thorough” one but in his opinion it has not been working. In the weeks prior to his appearance on the show, the Slovenian public could see a battle going on between Zdravko Počivalšek and then Minister of Health Tomaž Gantar. Počivalšek was explaining that the country has to reopen some economics sectors otherwise the Slovenian economy will collapse. And at the same time Gantar was trying to implement an even stricter lockdown and saying that the current restrictions aren’t strict enough to fight the pandemic effectively. Minister Gantar’s party DeSUS has since left the coalition and a day later Gantar has resigned as Minister of Health.

Minister Zdravko Počivalšek on Studio City show on 7 December 2020

Link: https://4d.rtvslo.si/arhiv/studio-city/174737910

What is lockdown and why is the system not working?

We contacted minister Počivalšek via e-mail to get further information on his statement. In his response to our questions, given to us by his PR team, minister Počivalšek stated that his claim is “based on the adopted government decrees, which during the exposed period prohibited, for example, movement between municipalities, gathering, movement at night, operation of many service activities, etc.” The Minister also said that the country has a thorough lockdown and this claim is based on “comparison with other countries in the region, where certain activities that were banned in our country were allowed, such as restaurants and bars and certain segments of trade (eg the sale of technical goods)”.

He is acknowledging that other countries in the region also had thorough lockdowns but “by stating that the system is not working, it is crucial that despite the longest and most thorough “lockdown” compared to other countries in the region, we cannot see a reduction in the number of newly infected, hospitalized and people who need intensive care. Which is actually the basic purpose and goal of lockdown”.

We did not get the exact answer from the minister on our question about the longevity of the lockdown in Slovenia. Furthermore, his PR team did not provide us with the names of the countries with which he made the comparison. As it is hard to say which measurement marks the beginning of lockdown in different countries it is also hard to state when the lockdowns started in different countries and, consequently, we can not compare the longevity across Europe with accuracy. As a result of all the differences it is difficult to establish a clear definition of lockdown. Even minister’s definition is vague.

For further information about the effectiveness of measures in Slovenia we contacted the Head of the Center for Infectious Diseases at the the National Institute of Public Health but we did not get his answer.

The Oxford Coronavirus Government Response

Governments around the world all choose slightly different approaches to dealing with coronavirus outbreak. Because of the wide range of measures taken it is hard to compare different governments’ tactics in battling this pandemic. For the purposes of research and easier comparison of these measures around the world the researchers at Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford created a tool The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT)

OxCGRT systematically collects information on several different common policy responses that governments have taken to respond to the pandemic on 18 indicators such as school closures and travel restrictions. It now has data from more than 180 countries. Eight of the policy indicators (C1-C8) record information on containment and closure policies, such as school closures and restrictions in movement. Four of the indicators (E1-E4) record economic policies, such as income support to citizens or provision of foreign aid. Seven of the indicators (H1-H7) record health system policies such as the COVID-19 testing regime, emergency investments into healthcare and most recently, vaccination policies. The data from the 19 indicators is aggregated into a set of four common indices, reporting a number between 1 and 100 to reflect the level of government action.

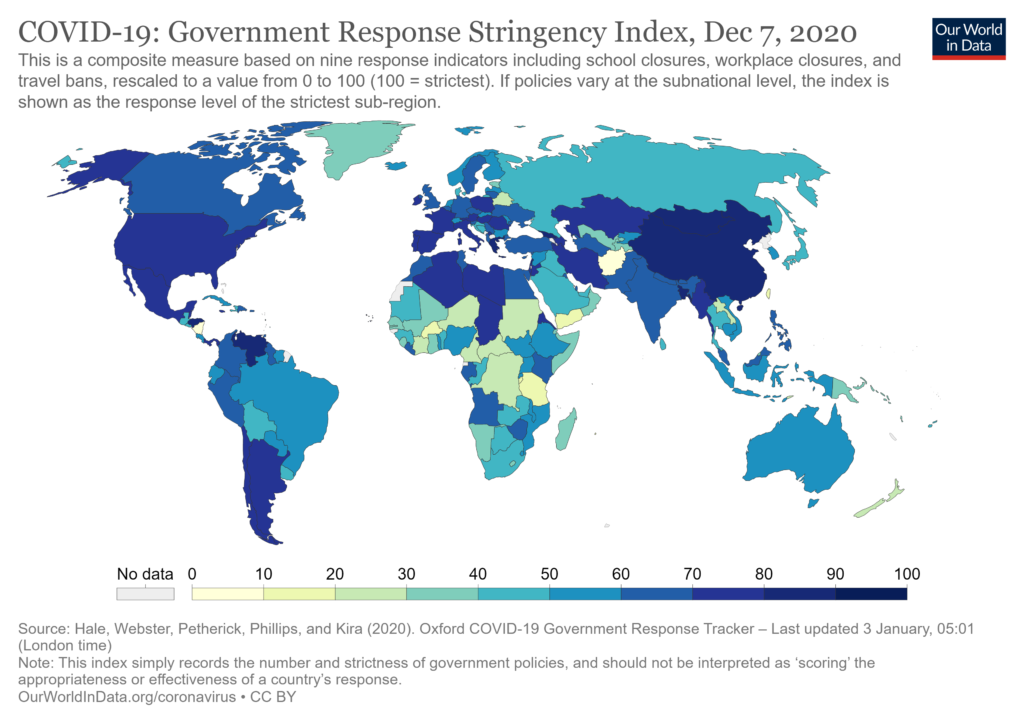

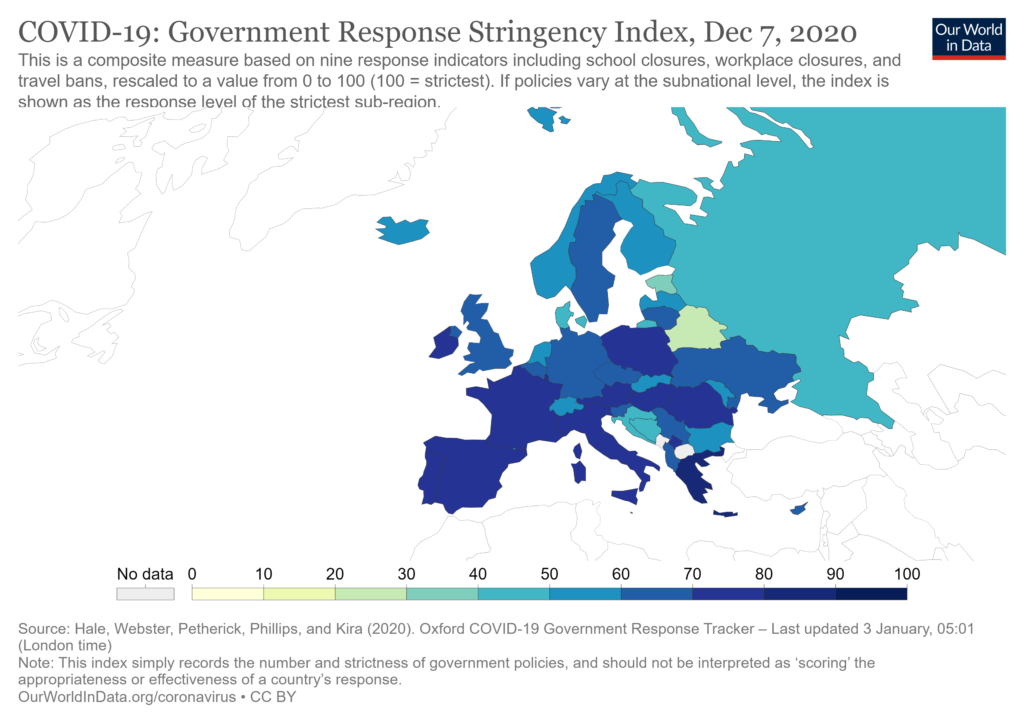

COVID-19: Government Response Stringency Index on 7 December 2020

Link: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-stringency-index?stackMode=absolute&time=2020-12-07&country=AUT~FRA~DEU~GRC~ITA~NLD~SVN~ESP~SWE~GBR®ion=World

Comparing stringency indexes in Europe

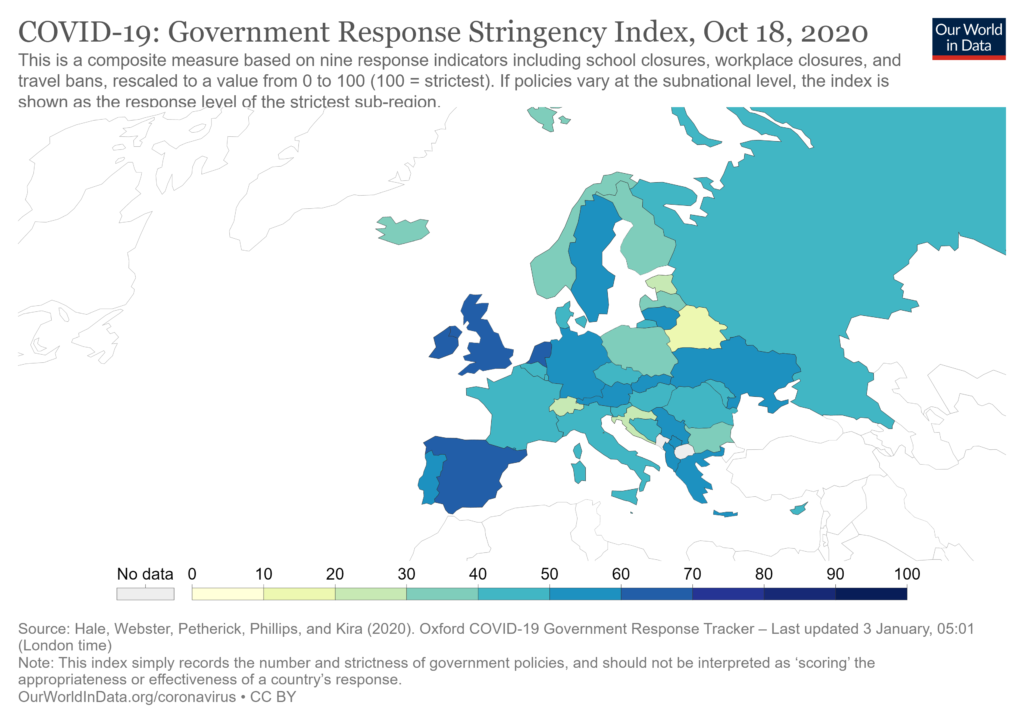

In his appearance on the show Počivalšek was talking about the second lockdown in Slovenia which officially started on 18th of October 2020 when the government declared an epidemic of the infectious disease COVID-19 in the territory of the Republic of Slovenia. On that date the stringency index for Slovenia was 47.22. Compared to some of the bigger countries in Europe on the same date Slovenia actually has one of the lowest stringency indexes. For example Spain had a stringency index of 64.35, Netherlands had 62.04, UK 60.19 and Austria 58.80. According to these numbers we can say that other countries in Europe actually had stricter measures in place before Slovenia declared the second start of the epidemic.

COVID-19: Government Response Stringency Index for Europe on 18 October 2020

Link: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-stringency-index?stackMode=absolute&time=2020-10-18&country=AUT~FRA~DEU~GRC~ITA~NLD~SVN~ESP~SWE~GBR®ion=Europe

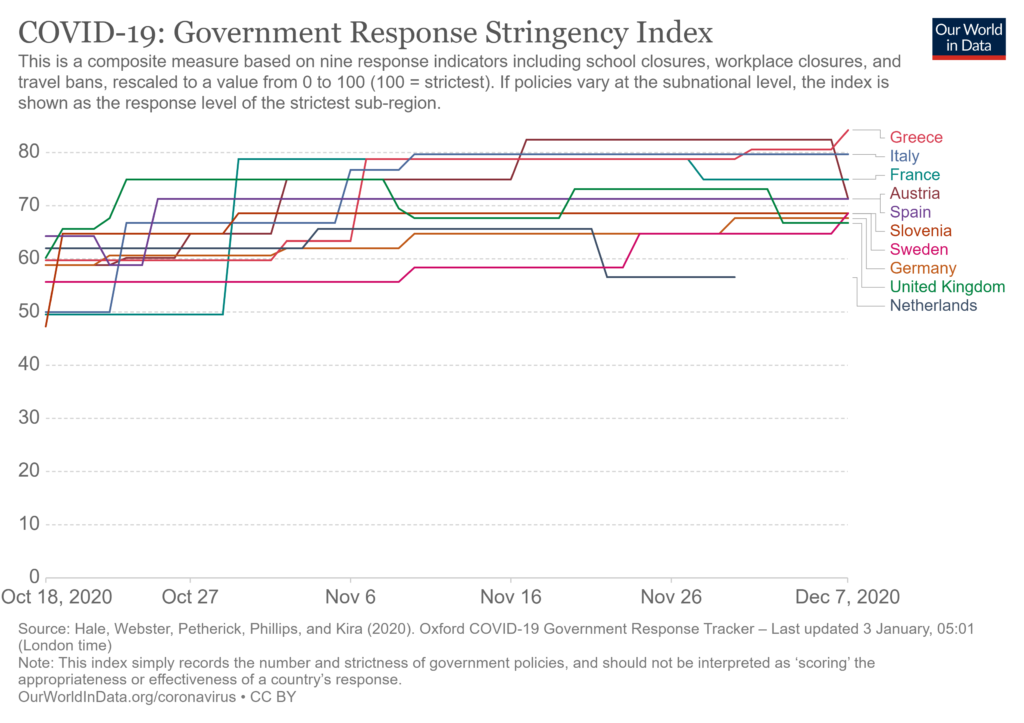

However, policies change every day. Slovenia implemented stricter measures the next day so the stringency index jumped up to 64.81. By the 7th of December Slovenia did not have a big change in stringency index, it only went up by cca. four points (to 68.52). As time went by, other countries also adapted their measures. For example, Spain had a stringency index of 71.30 (+6.95), UK had a stringency index of 66.67 (+6.48) and Austria which had a stringency index of 71.30 (+12.50).

COVID-19: Government Response Stringency Index from 18 October to 7 December 2020

Link: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-stringency-index?tab=chart&stackMode=absolute&time=2020-10-18..2020-12-07&country=SVN~DEU~FRA~GBR~ITA~NLD~SWE~GRC~ESP~AUT®ion=Europe

COVID-19: Government Response Stringency Index for Europe on 7 December 2020

Link: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-stringency-index?stackMode=absolute&time=2020-12-07&country=AUT~FRA~DEU~GRC~ITA~NLD~SVN~ESP~SWE~GBR®ion=Europe

Conclusion

In short, we can see that the original statement was vague and it did not state where on the spectrum Slovenia was located. Because of the constant changes in government measures around the world it is very hard to determine which country has the most thorough system or the longest lockdown. The word lockdown itself is vague and its meaning could differ between countries. For Europeans curfew could be the most thorough measure and most controversial while in other countries people do not oppose it. As our analysis shows measures taken in Slovenia have not deviated much from the measures adopted in other European countries across the autumn months. Thus, we confirm that the lockdown was indeed “thorough”, but it is not possible to confirm or debunk indefinetly whether it was also “one of the longest” because the lockdowns’ longevities are hard to estabilsh and compare across countries. On the basis of our analysis and reasoning of the factcheck, we find Počivalšek’s statement mostly true.

RESEARCH | ARTICLE © Anja Baškovč, Rebeka Krevs, Špela Plešnik, Maruša Slana

Leave your comments, thoughts and suggestions in the box below. Take note: your response is moderated.