As climate change becomes ever more apparent, calls for action and consistent measures are multiplying. Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), says as part of the launch of the UNEP Emissions Gap Report (EGR21) that to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, we have eight years to nearly halve greenhouse gas emissions. This statement is correct, even if it is the least we can do.

Six days before the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, UNEP released the 2021 Emissions Gap Report in a high-level online press conference with UN Secretary-General António Guterres and UNEP Executive Director Inger Andersen. The report’s contents are striking: all current climate pledges combined with other mitigation actions would result in global temperature rising by 2.7 degrees by the end of the century. This would be far beyond the goals of the Paris Agreement and would have catastrophic consequences in the Earth’s climate.

After the report was published, a quote from Inger Andersen travelled around the world: “To stand a chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, we have eight years to almost halve greenhouse gas emissions.” The direct quote originates from an article on the website of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that was published to go along with the EGR21. More specific information on when Andersen said the phrase is not available. If you read her foreword to the report and listen to the press conference on its release, it is noticeable that she never said the sentence that way then. It remains unclear whether an extra interview was given for the UNFCCC article or whether the quote is an adaptation for journalistic purposes.

However, in the context of reporting on the EGR21 she mentions that 55 percent of greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced by 2030 for the 1.5 degrees goal. “So we need to take a total of 55 percent off our current emission load on the least cost to pathway 1.5 degrees,” Anderson said during the press conference. In the Report she writes: “Reductions of 30 percent are needed to stay on the least-cost pathway for 2°C and 55 percent for 1.5°C. […] To get on track to limit global warming to 1.5°C, the world needs to take an additional 28 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) off annual emissions by 2030.”

But why is it 55 percent and not “almost halve” of the greenhouse gas emissions that must be reduced by 2030?

For the EGR21, scientists ran different scenarios in different situations. The current political course, the conditional contributions and the unconditional contributions that the signatories of the Paris Agreement promised are taken into account. The possible greenhouse gas quantities are expressed in the scenarios as “GtCO2e”, i.e. CO2 equivalents in billion metric tons, so that the warming effect of a greenhouse gas mixture can be indicated by a single number.

The figures show that in order to meet the 1.5 degree goal of the Paris Climate Agreement by 2030, 17 to a maximum of 33 GtCO2e annual greenhouse gas emissions may be emitted in 2030. The midpoint of this range is 25 GtCO2e – which is 42 percent of the estimated 60 GtCO2e in 2021. Or, if the different countries fulfil their unconditional nationally determined contributions (NDCs), the gap would be 28 GtCO2e in 2030 from the 52 GtCO2e expected by then. And that 30 or 28 GtCO2e are the 55 percent greenhouse gas emissions Andersen mentions in the press conference. If we achieve this reduction in emissions, the probability of limiting the global temperature to below 1.5 degrees by 2100 is 66 percent.

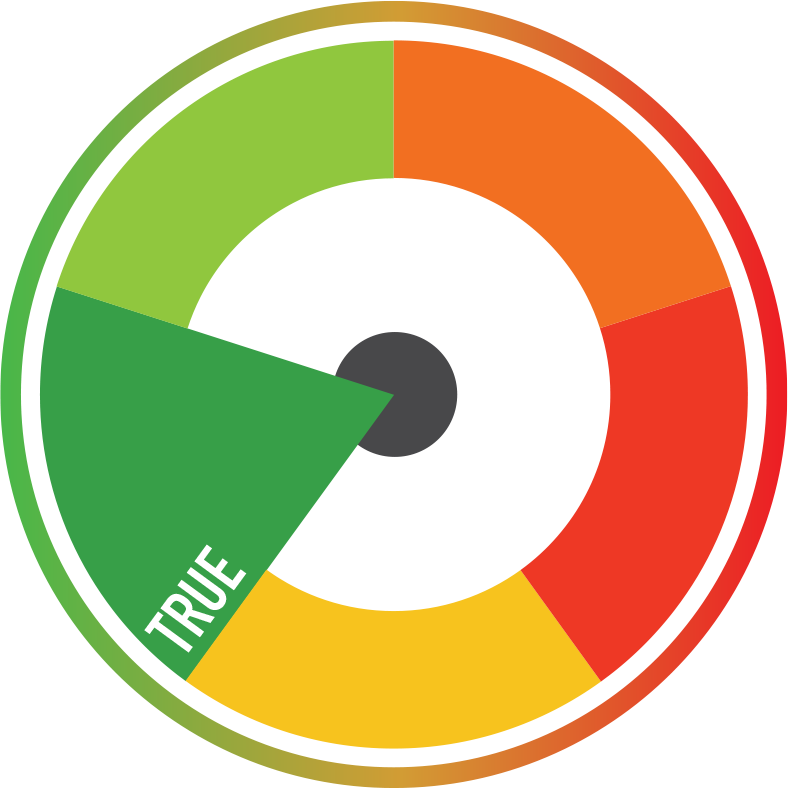

Different scenarios naturally lead to different probabilities. The EGR21 distinguishes between current policy and conditional as well as unconditional nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that are contingent on a range of possible conditions, such as the ability of national legislatures to enact the necessary laws, ambitious action from other countries, realization of finance and technical support, or other factors. The chart above shows how many emissions must be cut in 2030 additionally to the current path of the different scenarios.

But to at least have a chance of staying below the 1.5 degrees target, it is theoretically enough to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 28 GtCO2e to less than 33 gigatons in 2030. This reduction would correspond to almost half of the greenhouse gas emissions – both for the 55 GtCO2e of the current policy scenario in 2030 and the approximate 60 GtCO2e estimated for 2021.

All these numbers were aggregated with 100-year global warming potential values of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) and the IPCC Special Report on global warming of 1.5°C (IPCC SR15). The AR4 IPCC of 2007 expects global greenhouse gas emissions to be around 50 gigatons in 2030, and current UN calculations support this estimate. However, in this IPCC scenario, if emissions exceed 50 gigatons in 2030, the very best-case scenario is 1.8 degrees of global warming by the end of the century. The IPCC SR15 pathways for limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees, however, identify a range of between 25 and 30 GtCO2e to reach by 2030.

Conclusion

The numerical ranges of the IPCC 2018 and EGR21 overlap at 25-30 GtCO2e greenhouse gas emissions maximum to be emitted annually in 2030 to meet the Paris Climate Agreement. Thus, under the current policy scenario, we would need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least an additional 25 GtCO2e in 2030 to achieve the goal of 1,5 degrees. This would correspond to approximately 45 percent, or almost half. If we start from the nearly 60 GtCO2e greenhouse gas emissions in 2021, they also only need to be reduced nearly half by 2030. Consequently, Inger Andersen’s quote is correct.

RESEARCH | ARTICLE © Jana Prochazka, Stuttgart Media University, Germany

Leave your comments, thoughts and suggestions in the box below. Take note: your response is moderated.