On 26th November 2017, now-Italian Minister of the Interior said: “If elected, the centre-right government must guarantee 100.000 expulsions per year, in order to get half a million irregular migrants back to their countries in five years”. His promise has turned out to be false.

The immigration issue in Matteo Salvini’s political campaign

Immigration was one of the most covered issues of Matteo Salvini’s political campaign in early 2018. According to him, setting arrivals by sea to zero and increasing the number of repatriated migrants was a priority for the country’s welfare.

Long before becoming Minister of the Interior, Salvini already spotted some essential conditions to achieve his goals. First of all, he said, it was necessary to increase the number of the Identification and Expulsion Centres and to make the management of immigration shelters more transparent. In addition, he said he wanted to build other shelters under UN protection in Libya, to close more bilateral agreements for repatriation, to stop NGO ships’ arrivals to Italy and to change the procedures for refugee status’ recognition or revocation.

Also, Matteo Salvini promised several times that he would send back to their countries 100.000 people per year, a number he lowered just a few months after his election.

How Salvini’s promises changed through the years

On 26th November 2017, now-Italian Minister of the Interior said: “If elected, the centre-right government must guarantee 100.000 expulsions per year, in order to get half a million irregular migrants back to their countries in five years”. Not much later, on 11th December, he said again he would have asked his allies to sign an agreement on these numbers.

But no more than a year later, on 28th September 2018, Salvini said something very different: it would have been easy, he told the press, to send back to their homeland at least 4.000 people per year.

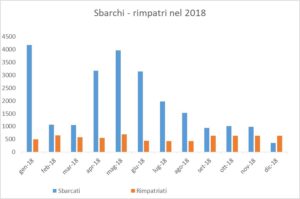

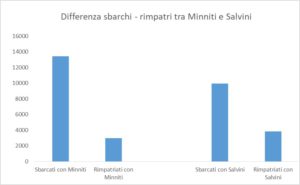

Figures published by the Ministry of the Interior show that 2.833 people have been returned to their countries in the first semester of 2018 (1st January – 31st May) while from 1st June to 31st December, under League-5 Stars Movement cabinet, the number has risen to 3.626. Altogether, 6.459 people have been expulsed from Italy in the whole 2018, more than the 4.000 promised in September 2018 but far less than the 100.000 promised in 2017.

Furthermore, according to latest data from Eurostat (Eu’s office for statistics) only 16.899 of 530.000 irregulars have left Italy between 2015 and 2017, while expulsion injunctions amount to 95.910. This means the number of people actually sent away from the country is far less than it should.

Matteo Salvini versus Marco Minniti

Lots of comparisons have been made in Italy between Matteo Salvini and the former Minister of the Interior, Marco Minniti (Democratic party).

The immigration bill signed from Minniti in 2017 led to an expansion of the shelter facilities. In replacement of the four existing Cie (Centres for identification and expulsion) the government created twenty “Cpr”, permanent facilities for repatriation, one for each region. Altogether they can host 1600 people, for a total cost of 19 million euros. The Conte cabinet, in charge from June 2018, approved the so-called “Decreto sicurezza” (Security bill), which expanded the maximal stay in the Cprs from 90 to 180 days. The bill also establishes that, in case of no place available in those facilities, migrants can be detained in the border offices. In addition, it raises the funds stored for repatriation, although they are being invested from the government in a very new way: if the former cabinet wanted to launch a plan to encourage voluntary repatriation, the actual Minister is keen to spend this funds for sending migrants to their countries, whichever the way.

Why repatriating migrants is so hard

There are two different kinds of repatriation: voluntary repatriation and forced repatriation. The UNHCR (United Nations’ High Committee for Refugees) sponsors the first one, encouraging instruments like the geo-and-see, short stays of the refugees in their homeland to consider the safety conditions.

A plan of voluntary repatriation was put into effect worldwide in 2015, but it’s still not an option for a lot of migrants due to conflicts in their native countries, which put on place different risks and threats. Apart from UNCHR, there are various non-profit-organizations that deal with repatriating migrants that could be reintegrated in their homelands. These associations usually guarantee a plane ticket and a funding of €2000 to start a business. In Italy, the AVR (Assisted Voluntary Return), financed the assisted return of 270 citizens from Colombia, Ecuador, Perù, Morocco, Nigeria, Ghana and Senegal. In 2017, CIES (Centre for Information and Development of Education), CIR (Italian Centre for Refugees) and GUS (Human Solidarity Group) developed three different programs funded by EU and the Ministry of the Interior’s Asylum Migration and Integration Fund, bringing back home almost 300 migrants from different countries in North Africa.

Forced repatriation, instead, depends on several laws and bills that tried to regulate its procedure, such as the so-called “Minniti-Orlando” bill on immigration (that includes, among other measures, the increasement of the shelters’ net and the introduction of voluntary work for migrants).

Both voluntary and forced repatriations share the same huge problem: they are really expensive (from Euro 3,000 to Euro 5,000 per person, due to charter flights and safety measures), as was iconically shown in 2006, when 29 Tunisian citizens were repatriated at a cost of Euro 115,000 for the Italian government.

For the year 2019, the Ministry of the Interior allocated Euro 1.5 million, an amount sufficient to cover just 500 travels. But it’s not only money: time is also a much-needed resource. Talking about arrivals from Tunisia, Matteo Salvini said that we would need 8 years to repatriate the 4,000 migrants illegally landed in Italy. It is to be seen if this statement can be considered an admission of how difficult is the management of this repatriation system in terms of money and time.

In conclusion, Matteo Salvini had promised to repatriate 100,000 migrants per year, but in his first six months of government he only sent back 3,626. Therefore, his promise is false.

Leave your comments, thoughts and suggestions in the box below. Take note: your response is moderated.