Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán launched the European Election Campaign of the political party Fidesz. Throughout his speech, he claimed that: “In 2010 the Hungarian economy was about half the size it is today. To put it another way, in fourteen years we have almost doubled the size of the Hungarian economy. […] Today Hungary’s achievements are under threat from Europe, from Brussels.” We find this claim to be mostly false.

Orbáns’ bold claims on economy

On the occasion of launching the European election campaign on 19th April 2024 in Millenáris (Budapest), Orbán made several claims regarding Europe’s economic decline. He further highlights Hungary’s numerous economical achievements and states that the Fidesz Party represents the best political community in both Hungary and Europe. Furthermore, he affirms that the Brussels leadership has to be replaced, pointing that Hungary occupies a critical role in protecting freedom in Brussels, following the Party’s achievements in Hungary.

Orbán pointed to Hungary’s economic growth, which has almost doubled in the past 14 years, although it is unclear what he specifically considers under the umbrella of economy and does not provide a source for his statement. Therefore, a fact check is necessary.

Evaluating Hungary’s economic growth

A key indicator of economic growth is the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Hungary has seen a steady increase in its GDP, yet it is crucial to acknowledge that other aspects of the economy also play significant roles beyond GDP.

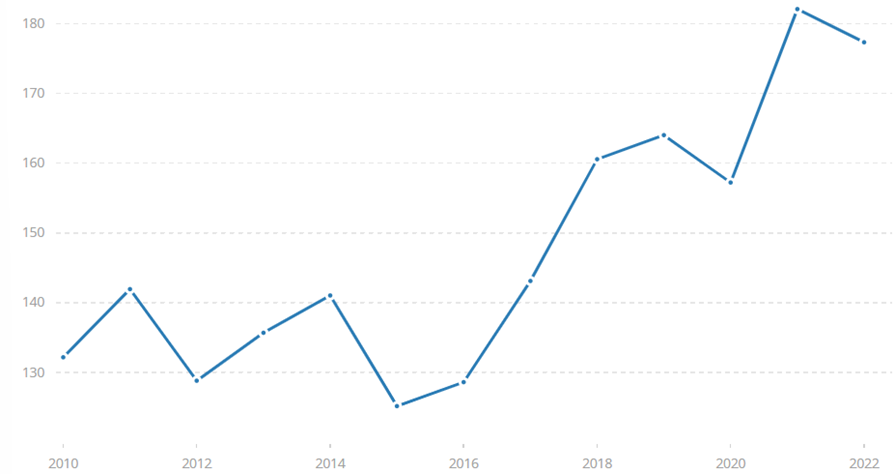

Based on World Bank data, Hungary’s GDP in 2010 was approximately $132.18 billion, while in 2022, the most recent available figure, it was approximately $177.34 billion. The percentage increase in GDP between 2010 and 2022 was approximately 34.17%, indicating a substantial increase but not a doubling of the economy.

According to Eurostat’s data on real GDP growth rates, Hungary’s GDP stood at 46.8% in 2012. It grew consistently until 2015 but has experienced a decline since then, registering 42.4% in 2023. Comparatively, Norway recorded the highest GDP growth rate in the European Union at 62.9%, followed by Finland at 52.9%, and Denmark at 50.3%. Belgium and Austria also showed significant figures, registering GDPs of 50.1% and 49.5%, respectively.

A look at other economic relevant indicators

The minimum wage, pensions and the unemployment rate are other critical economic indicators for Hungary, as together they provide a broader picture of the country’s economic health and population’s well-being. Together, these indicators can help to assess economic resilience, inequality and the effectiveness of economic policies in Hungary.

According to Wage Indicator, the current national minimum wage in Hungary amounts to 688 EUR (266,800 HUF) per month. Wages in Hungary reached an all-time high of 1.697 EUR in December 2023 and dropped in February 2024, amounting to 1.567 EUR.

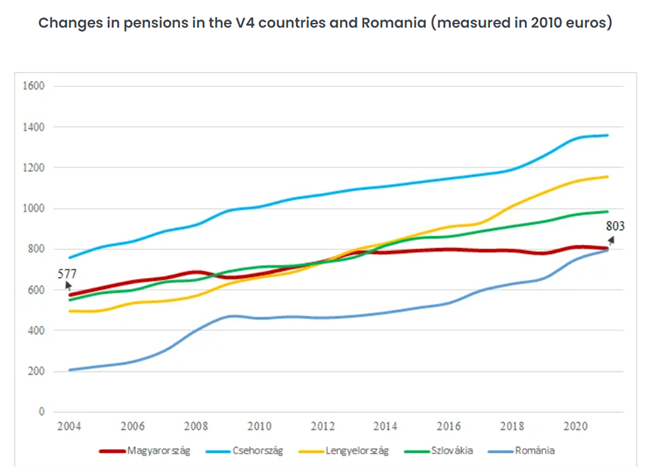

Pensions are one of the parameters that have to be regarded to offer further insights into Hungary’s economy. In euro terms, Hungarian pensions have increased by 39%, roughly matching inflation in the euro area.

Graph 2: Evolution of pensions in the Visegrád Group countries and Romania – GKI based on Eurostat 2024

Although the Hungarian and Polish figures were essentially the same in 2004, by 2023 Polish pensioners could manage with one and a half times the domestic amount. In 2004, the Romanian pensions did not even reach half of the Hungarians, but by 2023 they were already 37% higher than the Hungarian ones, while the Czechs continued to increase their advantage.

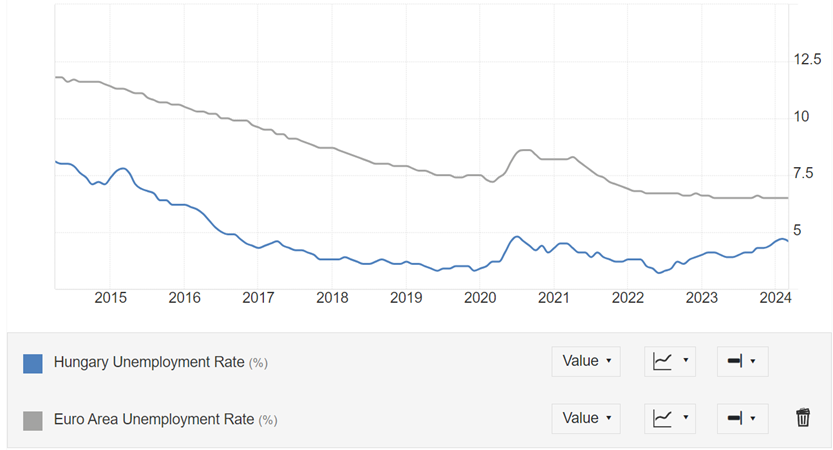

Trading Economics reports that the Euro Area average rate of unemployment is 6.5% according to the latest statistics, meanwhile the Hungarian rate is in a better situation; with a percentage of 4.6%.

Hungary’s economic landscape: Consumption patterns, income disparities and inflation challenges

Hungary’s economy is better put into context when looking at people’s consumption habits. Experts from the Magyar Nemzeti Bank (MNB) have analysed the situation. The consumption power of the Hungarians was the second lowest in the EU in 2022, with only Bulgarians spending less. MNB analysts have concluded that this happens because Hungarian households have low incomes. This is partly due to Hungary’s economic structure: sectors lacking competitiveness result in lower incomes, and 3-4 % of the GDP is annually emigrated abroad due to national indebtedness and remittances from foreign companies.

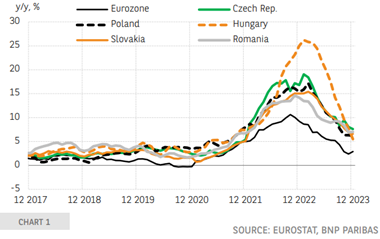

In recent years, household incomes in Hungary have surged by 140% in HUF terms, marking the highest increase in the EU. However, this growth doesn’t translate impressively when measured in EUR. In EUR terms, the average gross domestic earnings are less than half the EU average and only 64% in purchasing power parity terms. Inflation has also played a part in this. Since joining the EU, Hungary has witnessed the swiftest rise in consumer prices among its ten simultaneous joiners. After the COVID-19 crisis, EU inflation jumped by 20%, leading to a 140% price hike over two decades, compared to the EU’s 240% increase during the same period.

In December, inflation in Hungary continued to decline, with the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (HCSO) reporting better-than-expected figures. Compared to November, headline inflation dropped by 2.4 percentage points to 5.5%, due to a high base from the previous year and reduced overall price pressures. Despite this positive end to the year, 2023 will be noted for its extreme inflation, with an annual average of 17.6%.

The Hungarian economy is especially affected, with inflation amounting to 25.2% in March 2023, while the European average was 6.9%, according to Trading Economics.

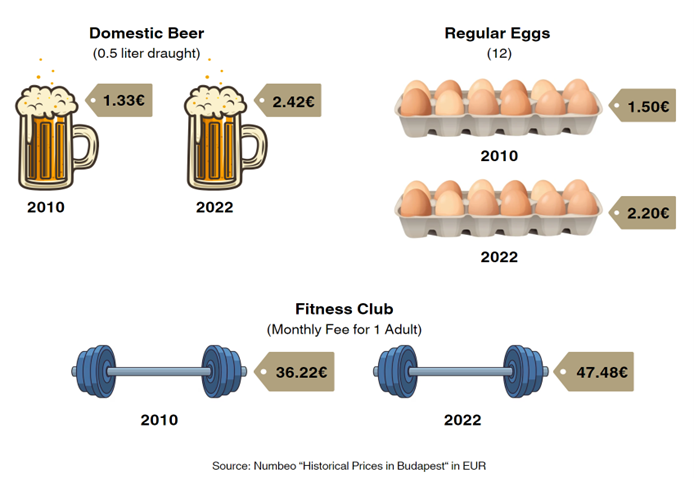

Over the past two decades, the relative price stability of marketed goods and services like clothing, communication, and catering in Hungary has been notable compared to the EU average in terms of purchasing power parity. However, food, which constitutes 21.7% of household spending, tells a different story, according to the MNB experts. While in 2004, food prices were two-thirds of the EU average, by 2022 they rose to 90%, and recent calculations by the MNB indicate they reached 96% of the EU average. This suggests that life in Hungary has become as expensive as in the EU, despite incomes being only half to a third of the EU average.

Foreign and European investors forced to leave Hungary

European businesses operating in Hungary are facing more and more obstacles in the form of special taxes and restrictions. In his European election campaign speech, Orbán declared his aim to put Hungary before everything, saying: “God above us all, Hungary before all else!”.

According to an article in the German magazine SPIEGEL, foreign companies in the construction, communications, transport, retail and financial sectors have so far been particularly affected, while the automotive and defence industries in Hungary are being offered better conditions. SPIEGEL quotes a letter from five members of the European Parliament to Commission President Ursula von der Leyen that this was a “blatant violation of the freedom of establishment, the right to property, the principles of fair competition and other core elements of the common internal market” and that the “Commission must impose fines immediately”.

The situation in Hungary also raises questions about solidarity and cooperation within the EU. As the Union seeks to promote economic integration and common values, such actions by a member state like Hungary put the unity and functioning of the internal market to the test.

Conclusion

Viktor Orbán’s claim on Hungary’s economic growth is mostly false. While it is true that the country has known significant economic progress, it has not doubled in size throughout 14 years. The PM’s claim is vague, thereby not accounting for other factors such as inflation. Although he claims that Hungary’s achievements are under threat from Europe, European businesses that operate in the country are forced to struggle following Orbán’s attempts to increase the country’s independence.

RESEARCH | ARTICLE | GRAPHS: Alexandra Berzovan (Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania) , Zoe Goslar (Jade University of Applied Sciences, Wilhelmshaven, Germany), Marc Descals (Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Spain) and Ewan McNeill (Thomas More University of Applied Sciences, Mechelen, Belgium) with lecturer coach Tena Perišin (University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia).

This factcheck was produced during the Blended Intensive Programme EU Elections Lab at the School of Journalism in Utrecht, The Netherlands

Leave your comments, thoughts and suggestions in the box below. Take note: your response is moderated.