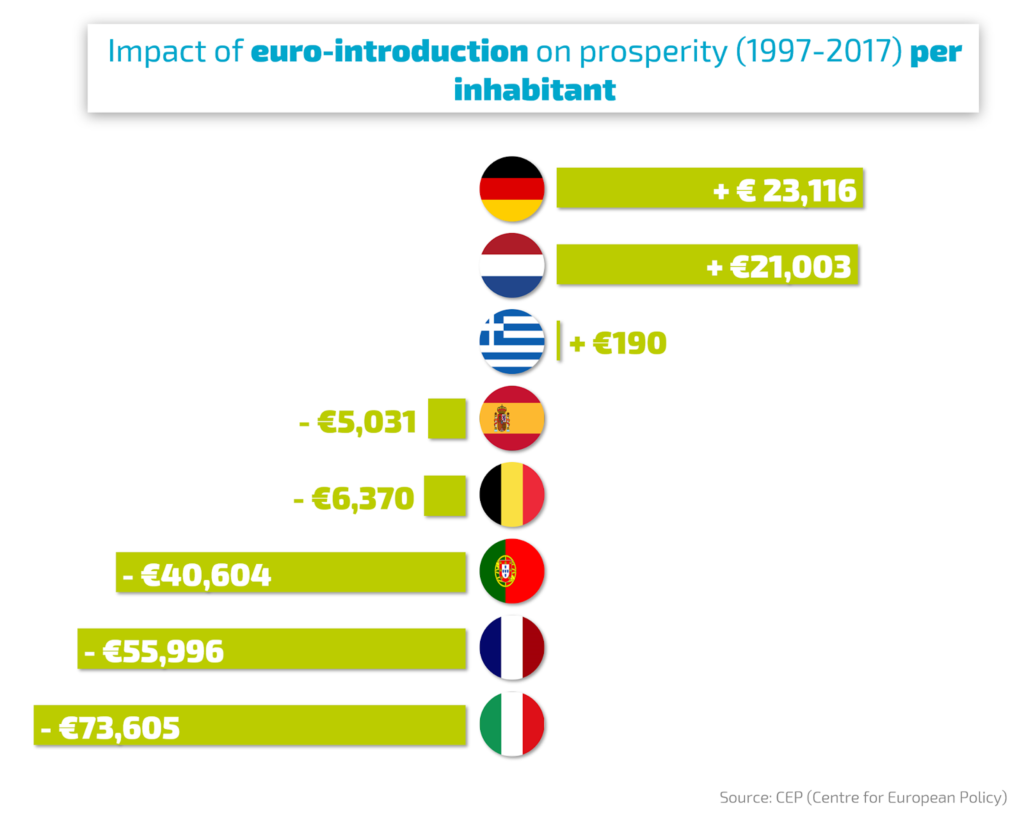

That is what the Belgian daily newspaper ‘Het Laatste Nieuws’ reported on February 25th . The article is based on a study from the German think tank CEP (Centre for European Policy) in which they researched whether the inhabitants of 8 Euro countries (the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany, Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain) have more money to spend now than before the euro was introduced as a currency. The original article shows us the following results:

The claim can be considered mostly false. The study shows “winners and losers” after 20 years of the euro. Some countries have seen a rise in prosperity per inhabitant while others have seen a (dramatic) reduction in prosperity per capita. The research conducted by CEP was considerably criticised by other academics.

Liberal colour

The study on which the article is based is of a strong neoliberal think tank. The chairman of the CEP (PROF. DR. LÜDER GERKEN ) is also chairman of the Friedrich-August-von-Hayek-Stiftung. Friedrich Hayek is a well-known political philosopher and economist of the twentieth century. He is regarded as one of the founders of modern day neoliberalism. Moreover, the German press also says that the CEP is considered quite liberal. As stated in the first lines of this article by Anja Ettel and Holger Zshäpitz from the German medium Die Welt: “The Freiburg Center for European Policy, CEP in short, a think tank known for their strict ordoliberal standpoint, has conducted research on the balance of the euro for every memberstate”.

The way the research was conducted

Their way of researching is not really waterproof. They work with control countries outside the euro zone and then compare the evolution of the GDPs with their corresponding eurozone countries: the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany, Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain respectively. But Eurostat didn’t publish data on the GDP of the euro countries before 2009, yet the study says that they start comparing the euro countries with their control countries from the moment the euro was introduced which was way before 2009 and the researchers do not explain in their study how they might have gotten the data for the GDPs of the countries from any other source either. Eurostat probably has data on the GDP of each euro country from before 2009, but it was not published on their website when we checked.

The study explains that the loss (or gain) of prosperity was calculated by assigning each of the 8 euro countries surveyed a number of control countries that had roughly the same evolution in GDP up to the point at which the euro was introduced. Then, on the basis of the evolution of the GDP of these control countries, it was calculated what the GDP of the euro countries could have been if they had not started using the euro as a currency. That way they could see whether the inhabitants of the euro countries would be “richer” or “poorer” without the euro. The problem here is the following: the control countries must meet a number of requirements, one of which is: “only countries that have not been affected by major country-specific shocks during the whole of the relevant period – 1980 to 2017 – can be considered as such shocks may distort the results”, according to the study. However, it never defines what such a “shock” is.

Inadequate methodology

This problem was also mentioned in the press. According to this opinion piece, by Marcel Fratzscher, member of the German institute for Economic Research (DIW). He considers the results of the study “not reliable” because the methodology is not suitable for the research. “The euro is not responsible for the debt crisis in Europe, but the mistakes of national governments”, he says. This remark by Marcel Fratzscher could mean that the way that the governments of each euro country choose to spend their budget has a bigger impact on the prosperity of said countries than the introduction of the euro itself. The article itself does not say that the euro is responsible for the debt crisis in the EU, but it can be interpreted as such, which would be incorrect according to Marcel Fratzscher. Even the president of the Munich Ifo Institute, Clemens Fuest, does not believe in the comparisons. The EU Commission also criticised the approach of the study. “A good analytical work and a robust methodology are a must to assess the causes of different policies and the development of the gross domestic product of a country”, said a spokesman for the Commission in Berlin. “The weak methodology of the CEP study is far from providing such solid analysis”, he added.

Opinion of an expert: Paul De Grauwe

We presented our factcheck to Paul De Grauwe, professor at KU Leuven and professor at the London School of Economics. He claimed that the journalist wrongly interpreted the study and therefore the title and the content of the article are false. “The Belgian has not become poorer since 1999 when the euro was introduced. The authors of this study concluded that Belgium’s per capita income has risen less rapidly than in this group of countries. There is a real difference between the control countries and Belgium’s per capita income of €6.370. But that doesn’t mean that the average Belgian citizen has become €6.370 poorer”, said De Grauwe. “On the contrary, according to The European Commission’s statistics (AMECO), the GDP per capita of Belgium rose from €29.300 in 1999 to €35.300 in 2018 (after adjustment for inflation), a real increase of €6.000,” concludes professor De Grauwe.

Conclusion

The opinions of experts like Marcel Fratzscher and Paul De Grauwe prove that multiple interpretations of CEP’s research are possible. The study itself was conducted correctly, but the interpretation of the study results by “Het Laatste Nieuws” was wrong. The Belgian citizen did not become poorer. Moreover Marcel Fratzscher’s opinion raises the question whether the introduction of the euro itself is the cause of these study results or whether it is more likely because of the way countries spend their budgets. We can assume that most of this claim is false. We didn’t find similar studies or numbers of other organisations.