In a column published by The Guardian, former universities minister Chris Skidmore makes the claim that there’s a higher risk for poorer students dropping out if universities shift online. This article—based on a study from 2017—was posted 4 May, 2020 in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis forcing many universities to close and offer fully online courses. This statement was found mostly true.

The article opens by describing the current state of universities as a result of the coronavirus shutting them down, which includes a bailout requested from the government for 2.5 billion euros. Skidmore then projects that the immediate future of universities is online—which could be a solution to the universities’ financial strain. But the cost of online learning at the university level falls on students from disadvantaged backgrounds, in Skidmore’s eyes. He cites and quotes the 2017 study done by Eric Bettinger and Susanna Loeb called “Promise and pitfalls of online education.” Skidmore spends a paragraph on the report, saying that poor students perform worse in online courses and are more likely to drop out of such courses. Then he moves on to his personal, anecdotal experiences as the former universities minister and opinion on how universities should move forward.

Sources

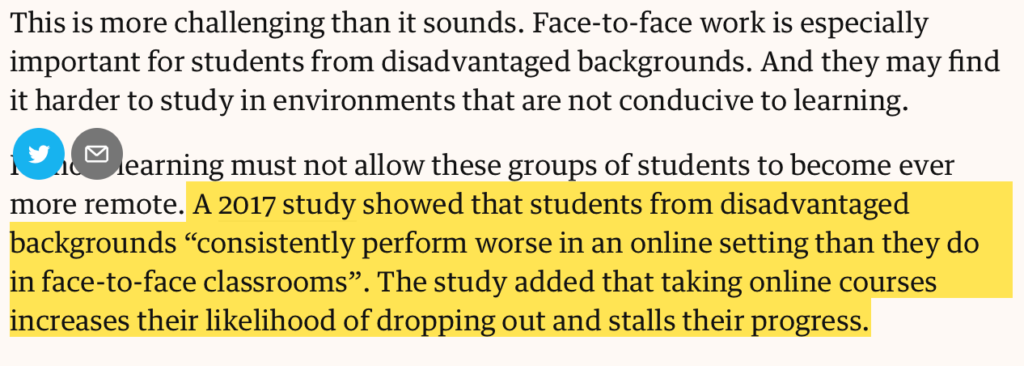

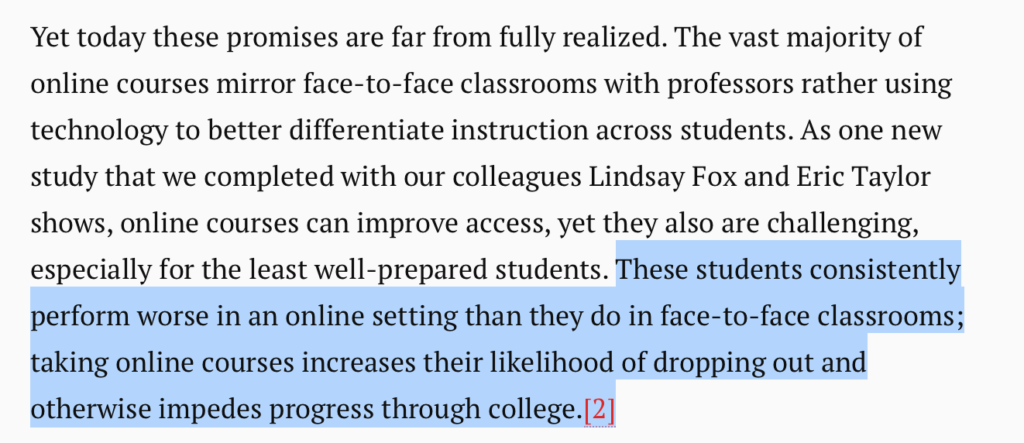

In order to verify this claim, it was important to look first at the source cited in the article. Nowhere within the study by Bettinger and Loeb are the words “poor” or “disadvantaged backgrounds” used to describe the students being discussed in the article. Instead, the authors use the term “least well-prepared” where Skidmore used the term “disadvantaged backgrounds.”

The highlighted texts show where (in yellow) Skidmore uses the study to back up his claim about students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The next quote, from from the study, shows where (in blue) the phrase is used to describe the students is “least well-prepared.”

Using the term “least-well prepared” covers a very broad category of students. Of course, this could include students from disadvantaged backgrounds, but since the authors did not specify, we cannot be completely sure this is the group they were referencing. To base the whole article off of this small section of the study and change the label of the students being discussed is a bit of a reach, even though Skidmore does make good points later in the article. It is also important to note that Skidmore’s only source is by academics from the United States. The concept of online learning is universal, but there are still distinct differences in the education systems in the United States and the UK.

Additional evidence

However, just because this study was a bit taken out of context here, does not mean that the overall message isn’t true. To determine if there is a higher risk for students from disadvantaged backgrounds dropping out of online university, more sources must be looked at.

According to a report by Spiros Protopsaltis and Sandy Baum, both underprepared and disadvantaged students underperform and experience poor outcomes on average in online courses. Both Protopsaltis and Baum are professors at universities in the United States. Part of their concern is that with cost-cutting efforts in education, well-intentioned moves to give greater access to university educations could lead to more disadvantaged students experiencing “cheap” and “ineffective” online education.

In another study called “Virtual Classrooms: How Online College Courses Affect Student Success”, which was conducted by professors at Harvard and Stanford, researchers found that students with weak preparation do not do well in online courses. The students in the study attended schools that disproportionately enroll low-income students. These groups of students tend to drop out of college at high rates.

The UK Institute for Fiscal Studies did a survey in regard to students’ success with at home learning due to the COVID-19 crisis closing all primary and secondary schools. They found from responses that students from better-off families have greater access to resources for home learning and are spending 30% more time on home learning than students from poorer families. Even though the students surveyed were in primary and secondary school, the survey responses support the idea that disadvantaged students are less likely to thrive in online classes.

There are several factors that could contribute to this overall conclusion that students from disadvantaged backgrounds do not perform well in online class settings. According to The Hechinger Report, maybe most significant is the fact that not all students may own their own laptop or have consistent access to Wi-Fi. Both issues would make it all but impossible to be successful in an online instruction setting. Another contributing factor in The Hechinger Report is that if the students come from low-income backgrounds, they likely work at least one job to pay the bills. This adds in another factor to juggling school and managing online coursework that is largely independent. For these students, most studies found that face-to-face instruction was a much more successful form of instruction.

Conclusion

The claim made by Chris Skidmore that there’s a higher risk for poorer students dropping out if universities shift online is found to be mostly true. This is not to say that all students from disadvantaged backgrounds cannot find success in online classes. However, the leading research makes the conclusion that on average, students from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to underperform in online courses.

RESEARCH | ARTICLE : Cora Hall

Leave your comments, thoughts and suggestions in the box below. Take note: your response is moderated.