At the end of February, British Prime Minister Theresa May posted a video on her Twitter profile containing a number of statements. She talked about increased employment, increased wages and reduced national debt. Research has shown that this is mostly true.

“We have more people at work than ever before.”

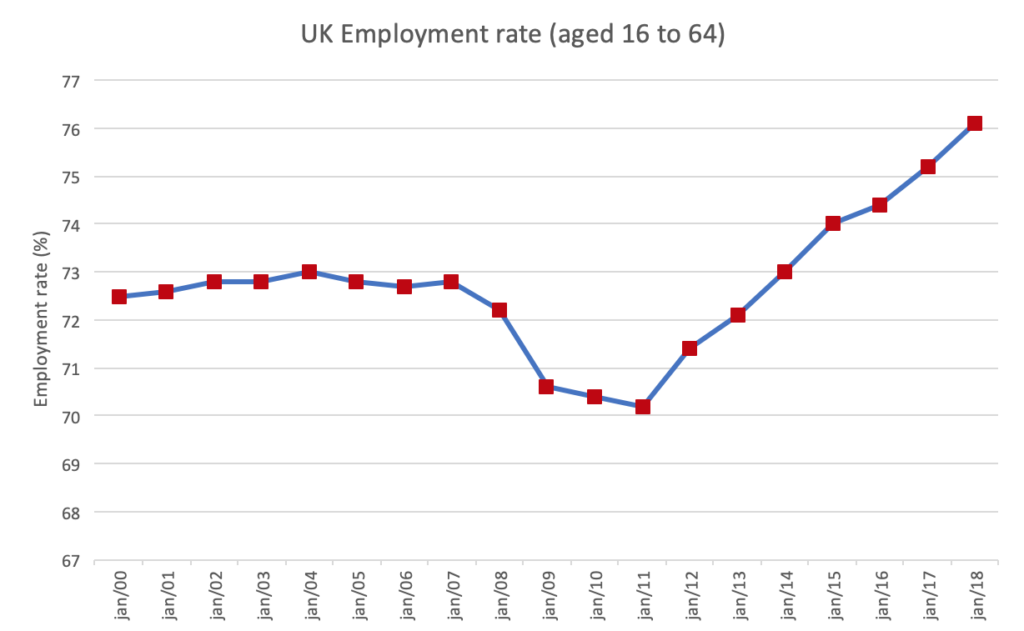

A first thing Theresa May said, was “we have more people in work than ever before”. The British economy looks positive at the moment. People are at work, wages are rising and the British labour market continues to run. So there seems to be no problem.

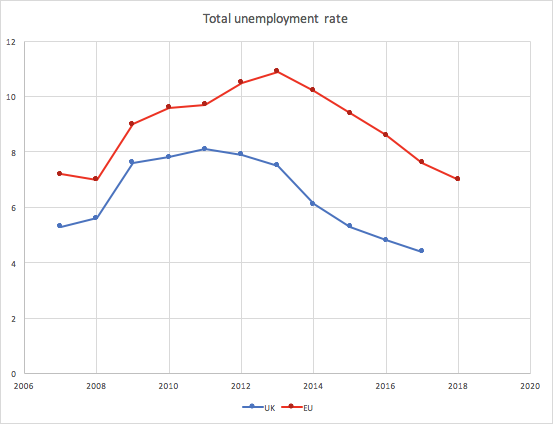

In addition, unemployment in the United Kingdom has fallen. We see that in the graph below. In 2011, 8.1% of the British labour force was unemployed, in 2017 this had dropped to 4.4%. Unemployment in the UK is also low compared to the European Union.

Graph: Emma Roose – Source: Eurostat

To come back to May’s statement (“we have more people in work than ever before”), you cannot deny that she is right. Last year, 76.1% of the British workforce was employed, the highest employment rate in British history.

Even when we look back in time, there have never been more British people in work than in 2018.

To sum up, the unemployment rate is falling and the employment rate is rising. There are actually more British people in work than ever before. So we can conclude that Theresa May’s statement is right.

“We have wages growing at their fastest rate for a decade”

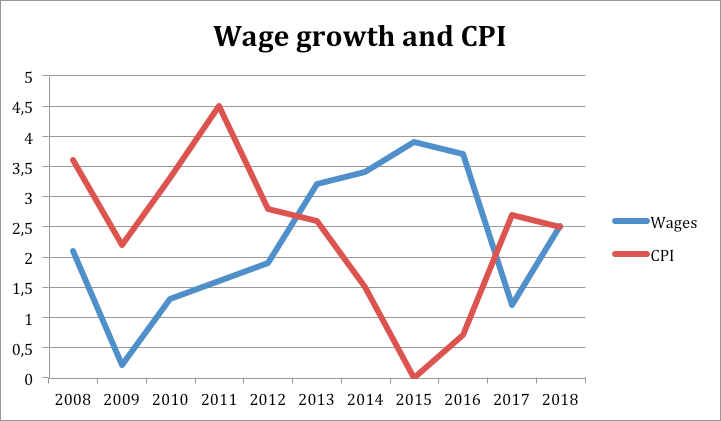

As a second proposition, Theresa May mentions that today’s wages are growing at their fastest rate for a decade. This statement sounds very positive, but in reality it is a bit different.

Graph: Astrid Vlaeminck – Source: Office for National Statistics; in 2015, a new index was drawn up and a new standard of 100 was created.

But according to Samuel Tombs, economist to Pantheon Macroeconomics, it will be difficult for the wages to increase even more. “Flows of people out of self-employment and into employee roles have remained strong, ensuring that record-high job vacancies don’t lead to spiraling wage growth,” he said.

May’s statement is therefore correct when she says that wages have been growing at the fastest pace over the past decade. But when we take inflation into account, this growth is a lot less spectacular than some would like to show. Real wage growth is thus rising less strongly than it appears at first sight.

“A debt falling as a share of the economy”

Has Britain’s public debt really fallen, as Theresa May claims?

From Eurostat data, we see a clear trend from 2007 onwards: public debt is starting to rise sharply. In 2007 the debt was 41.9% of GDP and in 2010 it was 75.6%. We see that the most remarkable increase occurred in the period from 2008-2009 to 2009-2010. During this period, the debt rose from 52.6% of GDP to 69.6% of GDP (“Gov.uk”). Ever since, we see that debts are still rising but much more gradually than before. In 2015 and 2016, we see an absolute peak moment with the national debt at 88.2% of GDP (Eurostat).

But in 2017, we see that the national debt gradually starts to decrease by 87.7% of GDP (Eurostat). On the website “Gov.uk” we can read that, last year too, the debts have fallen (85.8% of GDP in 2018 according to “www.ons.gov.uk”) and that this trend will continue, reaching 73% of GDP in 2023-2024. Compared to the peak moment in 2015-2016, this is still a significant decrease.

In “De Volkskrant” Frank Kalshoven (economist and columnist) says that Great Britain, with its national debt now close to 90%, is in the danger zone. It is also said that as a result of this, the British treasury no longer has any room to significantly support economic growth in the coming period. But according to current trends, the national debt seems to be reduced.

In other words: we see that the debt is still very high and was increasing until a few years ago, but has been stagnating for two years now. However, this stagnation is slow, but May has not lied when she says that the debts have fallen.

If we look at the three statements made by Theresa May, we can conclude that we can only nuance the second statement. Because of this, the statements of May are mostly true.