In Knack VIP (paywall), a Belgian weekly, Tomas Wyns said: “If the European Union sets standards for the energy-efficiency of electric devices, it also has an effect outside of the EU.” Wyns is a researcher at the Institute for European Studies, which is linked with Brussels’ university. His claim turns out to be true.

The European Union has imposed regulations considering the energy-efficiency of electric devices in the past, and will very likely continue to do so in the future. The manufacturers of electric appliances, inside as well as outside of the EU, have to meet those demands in order to be able to offer their products on the market, says Wyns, who specializes in climate and industrial policy and the innovation strategies that could be applied in these sectors.

Ecodesign requirements

The standards Wyns refers to are more commonly known as ‘ecodesign requirements’. Concretely, these are demands set by the EU for the energy-efficiency of electric devices, in order to improve their ecology and sustainability. The requirements can either be specific (e.g. a minimum value of recycled material) or generic (e.g. the product is recyclable).

The ecodesign requirements apply to a variety of electric appliances (e.g. boilers, computers, refrigerators, etc.). If any of these products fails to meet the standards, it can’t be distributed in the European Union. Hence, every electric device you own meets the standards, whether the producer is European, American, Japanese or based in any other country. Going from your South-Korean Samsung-television over your American iPhone to your German Siemens’ washing machine, every single one of these products has to fulfil the EU’s demands.

The Brussels effect

Wyns’ claim is based upon the ‘Brussels effect’ theory. This theory states that non-EU countries are inclined to copy rules set by the European Union, because of Europe’s market size and importance. Foreign manufacturers might miss a lot of profit if they don’t live up to the EU’s demands and, as a result, can’t offer their products on the European market.

So, the Brussels effect is a proven and repeated market mechanism. In fact, the European Union has the power to de facto, not necessarily de jure, manifest its laws outside its borders. The EU itself is also aware of this market mechanism. However, the European Union stresses that its regulations do not obligatory apply to non-EU countries nor will they automatically be copied by non-EU member states.

On the other hand, the European Union also experiences that other countries look up at Europe and take a leaf out of its book when it comes to developing their own policies considering ecodesign.

REACH, EU-regulations for the registration, evaluation and admission of chemical products, is an already existing example illustrating the Brussels effect. South Korea partly adopted the European Union’s plan, made some adjustments and called their version K-REACH.

Conclusion

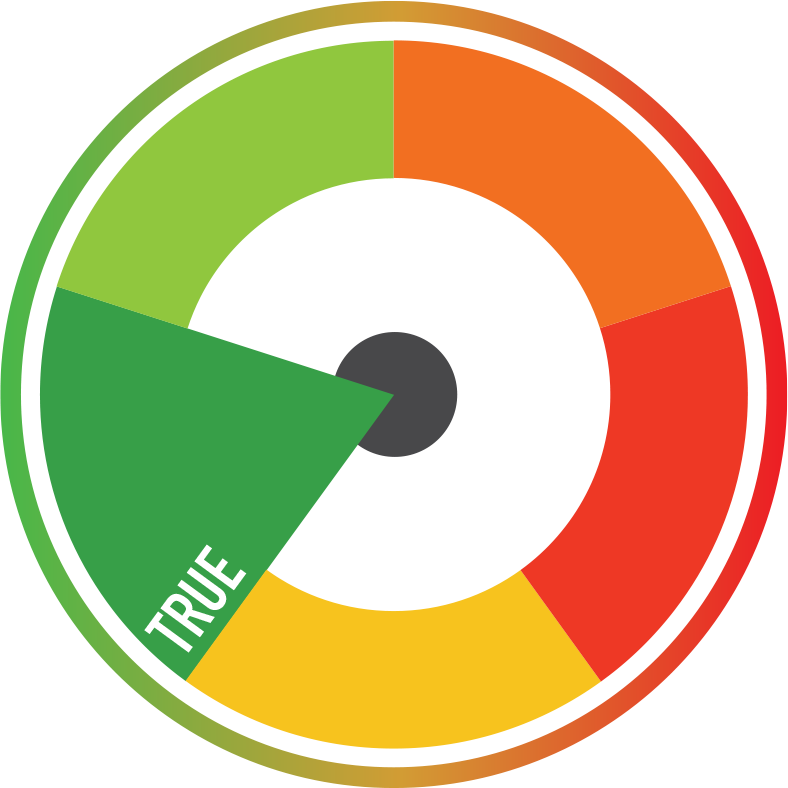

Wyns’ claim is based upon a proven and acknowledged market mechanism. On top of that, the European Union itself has experienced other countries adopting their regulations and therefore also recognises this phenomenon. In conclusion, Wyns’ claim is based on facts and supported by the European government. Therefor it is true.

Leave your comments, thoughts and suggestions in the box below. Take note: your response is moderated.

RESEARCH | ARTICLE © AP University College, Antwerp, Belgium