This blog post reveals why the tweet of an UN representative, claiming that just 0.3% of Covid-19 vaccines have been administered in lower-income countries, was not as easy to fact check as initially believed. Strictly, the statement can be seen as false, but does the complexity of the according figures even allow a definite judgment?

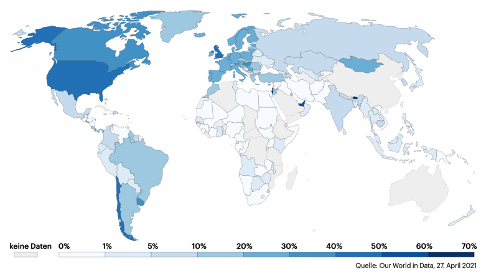

To get a global pandemic under control, it is essential that all nations act jointly to reach this shared goal of a sufficient global immunity to the virus. However, the Covid crisis disclosed the problems in such a cooperation and has revealed the differences that money makes. Now, it becomes apparent that in countries with a higher income much more vaccination doses have been given than in low-income countries.

This can be extracted from a tweet by Melissa Fleming, Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications of the UN. On May 8th, she tweeted “More than 80% of #COVID19 vaccines have been given in higher-income countries, compared with just 0.3% in lower-income countries”.

Apparently she refers to a press conference of the WHO from April 9th which states that “more than 700 million vaccine doses have been administered globally but over 87% have gone to high-income or upper-middle-income countries while low-income countries have received just 0.2%”.

Strictly comparing Melissa Fleming’s post and her original source, a small difference of 0.1 percentage points can be noticed. It raises the question whether the UN representative states wrong numbers in her tweet or if the difference is simply due to rounding or typing errors. This question has been dealt with in the corresponding fact check, but there are some more concerns.

How trustworthy are public persons’ tweets?

If even a tweet from the Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications of the UN is not exactly correct, what about other public persons’ or politicians’ tweets? How trustworthy are their posts? Can information from tweets by public persons be trusted or does there have to be a greater caution believing this kind of information compared to maybe newspaper articles?

COVAX as global distributor of vaccines

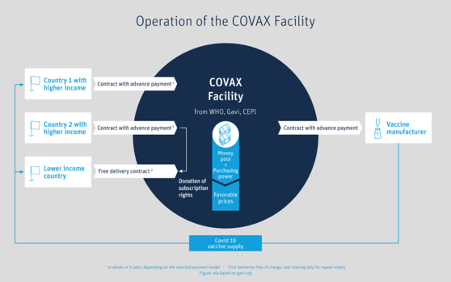

Most low-income countries get their vaccines because of COVAX. COVAX is an initiative led by WHO and COVAX Facility is working with vaccine manufacturers and procurement of COVID-19 vaccines doses. 190 of 200 Countries are participating, 98 Countries are high-income countries and 92 low, lower, and middle-income countries. For low-income countries it is possible to get vaccines for a low price or for free through COVAX. This system for low-income countries is only working because high-income countries are donating vaccine doses or money für vaccine doses. High-income countries can also get their vaccines through COVAX, they pay the normal full price, but most high-income countries are not doing that.

Until June 11th, more than 83 Million vaccine doses have been delivered through COVAX to the participating countries, of 131 supplied countries 92 low-income countries got vaccine doses. COVAX offers vaccine doses for at least 20% of the countries’ populations. To reach herd immunity at least 70% of the world population has to be fully vaccinated. WHO estimates that to reach that 70% goal, there is a demand of 11 Billion vaccine doses.

To this date there have been 2 Billion vaccine doses inoculated, but 75% of these doses in only ten countries. The USA, China and India alone used 60% of the worldwide 2 Billion vaccine doses. Another problem is the supply shortage of vaccine doses worldwide. According to a calculation by Ärzte ohne Grenzen in April the next three month COVAX lacks 211 Million vaccine doses because of supply shortage on top of insufficient planning. These numbers show that low- and middle-income countries have a hard time receiving the vaccines they need. An uneven distribution of vaccines makes it harder for low- and middle-income countries to beat the pandemic and they have to depend on donations and the willingness to help from other high-income countries.

https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/covax-initiative-erfolge-und-probleme-der-weltweiten.2897.de.html?dram:article_id=496465

Which degree of accuracy is even possible?

Another perspective on the topic and the initial tweet is to question how exact the numbers the WHO, Melissa Flemings primary source, provides, can even be. As for the huge scale of the WHO’s numbers and the difficulty with which numbers about administered vaccine doses are measured, do we have to see the 700 million as an exact number or rather as an estimation? This raises the question of whether Fleming’s statement can be called false at all. Statistics expert Prof. Dr. Ulrike Schleier of the Jade University in Germany underlines the complexity of such numbers and the resulting consequences for an evaluation: “Reported percent values about the status of current developments in public health policy can always only be estimations and these figures change on a daily basis. A deviation of a few percentage points is therefore to be regarded as completely normal.”

In conclusion, this blogpost reminds its readers to apply some caution when it comes to tweets depicting current and exact numbers for at least two reasons:

Even politicians or NGO officials may not always be completely right, may it be due to misunderstandings, rounding errors or real mistakes and misinformation.

On the other hand, maybe we have to be content with the provisioning of a tendency, as in the case with Melissa Fleming’s post, especially when it comes to such global numbers. Politicians in particular must be aware of their high level of responsibility. Especially when it comes to commenting on complex topics and figures in which they themselves are not experts. People usually rely on the word of leaders and take them for granted. As a citizen, one expects that the people in charge will also provide correct, truthful information. But this also outlines the general problem of the lack of transparency on the part of politicians. Politicians make themselve vulnerable by making such, even if small, mistakes. Political opponents could use these mistakes to divert the attention and change the subject. They focus on little mistakes and ignore the actual topic. By doing that, political opponents question the credibility of statements made by an actual credible politician. People no longer have the feeling that they can really trust them. Incidents like these are not helpful in this regard.

Caution and consideration in handling numbers about global vaccinations

In the end, it can be concluded that an assessment of the initial claim/the initial tweet “More than 80% of #COVID19 vaccines have been given in higher-income countries, compared with just 0.3% in lower-income countries”, was very difficult. Literally, the statement can be seen as false, because the quoted figures are not precisely correct, but then this is the case only for a certain day and may already change the next.

However, this assessment is in contrast to the complex issue at hand. The scale of the problem that Fleming adresses undeniably exists. With such complex figures that affect the whole world, it may be enough to judge the tendency. So we see the tendency of the original claim as largely correct.

RESEARCH | ARTICLE © Anna-Lena Gerlach, Nina-Julia Gleitsmann, Kira-Eileen Hillus, Rebecca Schöllchen, Sarom Siebenhaar, Celine Stephan and Vivian Kim Weiß, Jade University College Wilhelmshaven, Germany

This is the blog post linked to the cross-national fact check on the difference between vaccinations in hig-income and low-income countries by Jade University College Wilhelmshaven, Germany and AP University College Antwerp, Belgium

Leave your comments, thoughts and suggestions in the box below. Take note: your response is moderated.